By Akiko Macdonald

Source: Japan Forward | First published on October 4, 2017

Places where battles took place always have sad stories which we, as decent human beings, need to revisit to know how the soldiers fought and died on foreign soil. Some of the souls of the millions of fallen soldiers are still lost and have been forgotten by the developed countries that engaged in World War II.

Since Japan lost the war, sadly most Japanese have forgotten about the young men who fought for their country. They lack respect for their spirit and fail to honor them. This is due to the pacifist mentality that took hold after Japan was completely defeated in 1945, and which has continued for the last seven decades.

History tells us that foreign lands where indigenous people lived often became battlefields; in fact, the land never belonged to those invaders who were there for a short time, like Japan or, for many hundreds of years, like Britain. As far as the histories of Nagaland and Manipur are concerned, those regions had different kingdoms and consisted of many types of tribal villages, with cultures about which little was known and cultures entirely different from those in India.

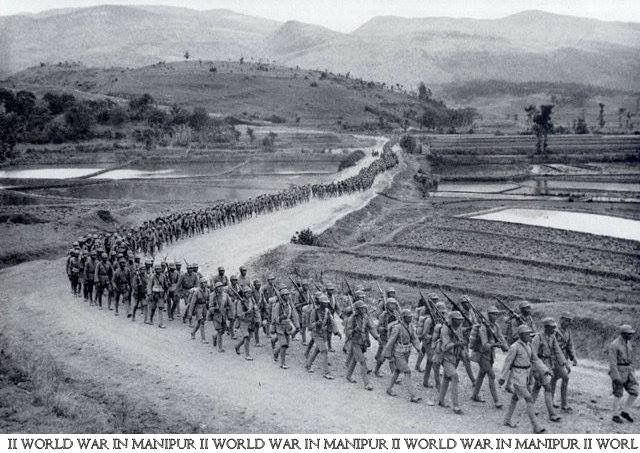

The Imphal-Kohima Campaign in 1944 was a turning point of the Burma War, and a turning point in the Pacific War that ended rapidly in 1945. The Imphal-Kohima Campaign was a massive gamble that the Imperial Japanese Army took, resulting in 30,000 to 50,000 Japanese soldiers dying either in battle or due to tropical diseases and horrendous starvation. A total of 320,000 Japanese soldiers were sent to the Burma theater, and nearly 190,000 Japanese soldiers perished. Those soldiers’ bones were never completely recovered nor brought back home to be properly buried.

The destruction that war brought to their land meant that many people were displaced by both nations. I believe that Japan and Britain have a responsibility for this, and yet both nations have done little to help restore or even to develop those former battlegrounds to help the people achieve prosperity like we have in our own country.

Why did my father survive this war, and, consequently, why was I born and why did I later get married to an Englishman? Is it correct to say that Japan was the aggressor that invaded British Imperial territory, or that Japan was the liberator of those Asian countries from Western colonization? The established narrative never considers that there might be other narratives to be heard.

Who saved India and Burma from what exactly and to what extent? And how do we look at them now since they became independent in the 1950s? There are many questions to be answered.

Between May and June this year I organized a camera crew from Imphal for a war history film, recording the battle locations and interviewing witnesses and touring battle sites. To find out what exactly the indigenous people thought about the war, I travelled to Imphal, Manipur state, and to Kohima, Nagaland state, both of which are in the north-eastern region of India where the Imphal Campaign took place.

Akiko Macdonald (center) was treated as VIP and escorted by the armed local police officers (Source: Japan Forward)

The film was aired on the nationwide TV on August 15th this year in cooperation with NHK. I wanted to stand where my father had stood at the Kohima battle site in June 1944 after he travelled through the jungle with the Japanese Army.

My father’s regiment was just about to charge toward the Kohima village where the British HQ was located for a final suicidal attack. They only had a few bullets left when, at the critical moment, his regiment was ordered to retreat by General Kotoku Sato. He survived because of this. The withdrawal was an extreme, unprecedented action and against superior orders, and it contravened the Japanese code of military conduct.

The people of Nagaland and Manipur are still living in poor housing using broken corrugated tin sheets and without electricity or clean water and decent drainage. Rubbish tips and contaminated muddy water are everywhere. Their plight reminded me of post-war Tokyo in the 1940s to 1950s. I felt absolutely desolate when I learned that the remains of fallen Japanese soldiers are still unearthed beneath the soil of those garbage tips.

My journey continued from Imphal to Kohima along unpaved roads, where the traffic is often disrupted by herds of cows standing stubbornly in the middle of the road. The roads are also flooded from time to time by overflowing rivers. Yet, the people we met were genuinely nice and kind to us. Why is that?

I saw the caste system still is at the center of Indian society. The religions, the tribalism, authoritarianism, the diversified but divisive cultures—these all create a gulf between rich and poor.

The ethnic and tribal conflicts continue in Nagaland and Manipur after 5 decades.

Wherever we went, they told us:

“Japanese soldiers were very disciplined and polite.”

“They came without rations and were very hungry. They asked us for food like rice with their military money, but the money was no use since they lost the war.”

“They were starving and took our food and killed our chickens and cows.”

“Britishers came to our villages before the Japanese came, saying, ‘Go to the jungle to hide from the invaders.’”

“They gave us a gun to kill the Japanese, but we only killed birds and animals. Later the Britishers bombed our villages and mountains. We lost everything after we returned to our village.”

“Japanese officers told us we are the same as them, and we came from the Mongolians to fight against white men and promised to build a hospital when the war was over.”

“We welcomed both Britishers and Japanese whoever they were, we did not know what WWII was.”

My view of achieving war “reconciliation” in the case of the Burma and Imphal Campaigns is to include the indigenous people in India and Burma where the actual battles took place. The problems of the post-war never can be resolved without considering where the battles took place.

Therefore, I have been working on Japan-India-UK war reconciliation since 2011 by communicating with the leader of a local volunteer group who lives in Imphal and excavates the battle sites where many Japanese soldiers’ artefacts and their bones are still buried. They discovered many undetonated bombs buried on their land, and the local villagers had many fatal accidents without knowing how dangerous those objects are. Those problems still exist.

British and Japanese knowledge of technology and engineering skills can help develop their infrastructure to improve their lives. Japan has now started to provide aid for young people from these states to travel to Japan, and it will support reconstruction of the Imphal-Kohima national road, which is nearly 150 miles long. This will create employment and business, shops which will generate wealth between the two states and even provide a connect from Myanmar to Imphal.

If they resolve the conflicts among themselves, there is hope that they can work together for the same goal to coexist regardless of their political orientations or religious denominations, and there is definitely great potential and opportunity for growth. I met many young volunteer groups in the two states and students at the universities. They are full of energy and enthusiasm to work and to take positive actions for their future.

I think Japan and Britain can push progress along and avoid the failures of the past. To exchange knowledge of transformative social engineering, based on experience, is the key to tackle the living conditions that they have now. There will be 25 young people coming to Tokyo in autumn this year. I am very pleased that they will have a great chance to recognize that things are so different from their own living environment. When I went to those states, I realized the war had not really ended for the people there.

If former adversaries are to offer solace for the sadness of both fallen soldiers who never had a chance to see peace and prosperity return, then those war-affected indigenous people must be included to engage in the process of war recovery for the sake of the lost souls.

This way, I believe, is the way to true reconciliation.

Akiko Macdonald is chairperson of the Burma Campaign Society (BCS) since 2008. It is composed of British veterans who inherited the Anglo-Japan reconciliation which began in 1983, contributing to the firm friendship between both countries. Akiko’s father, Taiji Urayama, 95, served as a lieutenant in the veterinary mountain artillery, Second Main Battalion of the 31st Regiment in the 31st Division of the 15th Army of the Imperial Japanese Army, in the Burma/Imphal and Kohima Campaign during WWII. In 2015, to mark the 70th anniversary of WWII, Akiko’s father and his UK counterpart Roy Welland shook hands at the British Embassy in Tokyo. In 2017, to mark the anniversary of the 73rd Imphal Campaign, Akiko was invited to visit Manipur by the state government, and also had an opportunity to meet the Nagaland Chief Minister when visiting Kohima in Nagaland, India. Akiko has been living in the UK since 1988 with her two grownup children and English husband.

What Does Your Face Say About Your Health?

What Does Your Face Say About Your Health? The last Konyak headhunters of Nagaland

The last Konyak headhunters of Nagaland The Top Viral YouTube Videos of 2017

The Top Viral YouTube Videos of 2017 An orbiting message of peace

An orbiting message of peace

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked (required)