By Bhavya Khullar

-

The caves of Meghalaya are home to species of blind fish, a type of loach.

-

Schistura larketensis or the Khung loach is the second species to be discovered from the cave systems of the Jaintia hills.

-

This species is particularly threatened by mining, pollution and hunting in the adjoining areas since its population size is very small.

A live specimen of Schistura larketensis. Photo by D. Khlur B. Mukhim.

A new species of eyeless fish has been discovered from deep within an extensive cave system in Meghalaya. The small, slender freshwater loach has been described from Krem Khung, a limestone cave situated about 1.5 kilometres from Larket village in the Jaintia Hills District of Meghalaya. Locally known as ‘tyrlen’, the scientists have named it Schistura larketensis, the ‘Khung loach’.

“When a torchlight is focused on the fish in an aquarium or its natural habitat, there is no visible reaction,” said study author Dandadhar Sarma, professor of Fish Biology and Fishery Science at the Department of Zoology of the Gauhati University in Guwahati, Assam.

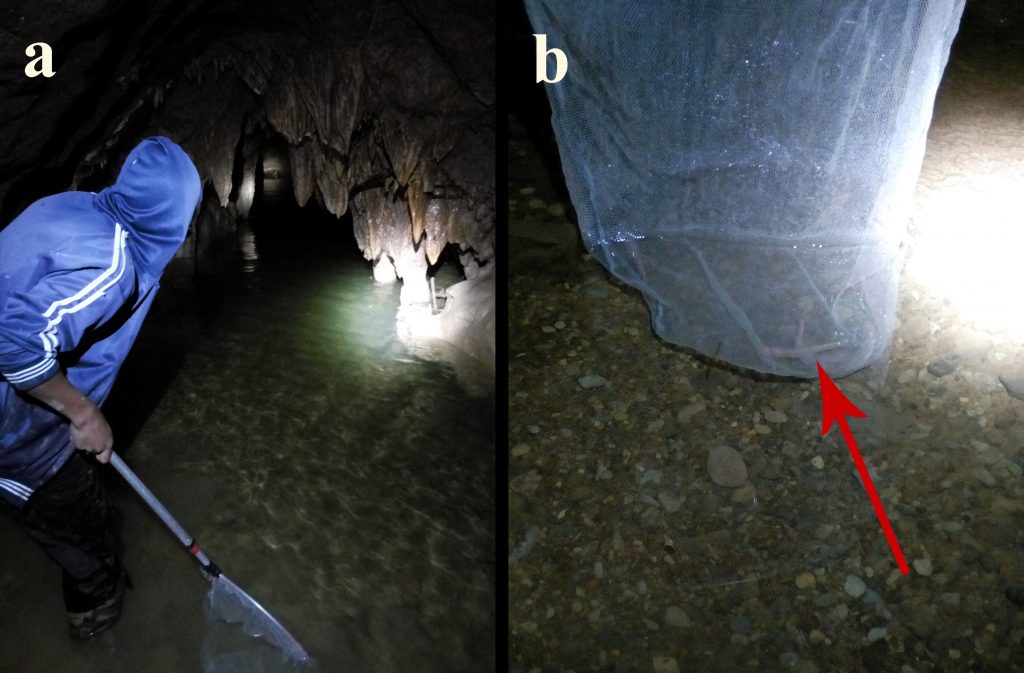

The blindfish was collected from a small stagnant pool, which was a few square metres in area and about 1 metre deep located in a wet passage some 500 metres from the main entrance of Krem Khung cave. The pool bed was sandy with scattered pebbles. Apart from the blindfish, scientists could see weakly pigmented crabs and crayfish, crickets, cockroaches and millipedes. “We are now trying to understand its role in the cave ecosystem and its biology,” adds Sarma.

Meghalaya has more than 1600 caves, with the Krem Liat Prah Umim Labit cave system in the East Jaintia Hills being the longest in the Indian subcontinent. The 30 km long cave system houses the Khung cave, which by itself is nearly 7350 metres long. It has a stream leading through the central passage that ends in a lake in its last segment, which drains to the Kopili River, a tributary of the Brahmaputra. The new species was found in one of the cave’s side branches, in a small pool. The water level of this pool fluctuates throughout the year. During the monsoons (between May and July), these passages flood, bringing in debris from outside, and the water becomes highly turbid.

Different caves, different species

a) Inside Krem Kung. b) A specimen of Schistura larketensis caught using a scoop net. Photos by D. Khlur B. Mukhim.

Khlur Mukhim, who first found the blind fish and collected the study samples is a caver, biologist and researcher. He has been a cave expeditionist for more than two decades now. “During these expeditions, he came across eyeless fishes in some caves,” said Sarma. Mukhim’s friends are credited with the discovery of its closest relative, the blind fish Schistura papulifera in 2007, from the Synrang Pamiang cave system in Meghalaya.

The fish remained misidentified as Schistura papulifera during the initial phases of Mukhim’s research work. However, when Sarma’s team examined specimens of S. larketensis, it was found to be significantly different from S. papulifera. In had no projections on its head, which confirmed that it is a new species. The scientists named it S. larketensis after its native village ‘Larket’ to encourage locals to conserve it.

Khung, where S. larketensis was found is just 32 km away from Synrang Pamiang, from where S. papulifera was first described. It is unlikely that the two caves are connected, as the East Jaintia Hills would form a barrier separating the two species. “S. papuliferais already a critically endangered and cave ecosystems are fragile, which is why intervention to conserve S. larketensis is required,” says Choudhury.

No need for eyes

The authors argue that being eyeless is a combined result of the effect of environment and natural selection. “In caves, where there is minimal or no light, the development of eye would be meaningless, and one would require or has to depend on other enhanced sensory systems to find food or mates,” they write in the paper.

“In our study, electron micrographs revealed the dense accumulation of large taste buds in and around the mouth, which could be an explanation for the loss of eyes in a completely dark environment that got compensated by the better development of other sensory features. In the case of our species—taste buds,” adds Sarma.

“As juveniles matured in captivity, the vestigial eyes were lost, leaving only small, faintly blackish spot-like depressions in adults, which indicates a progressive and total loss of this organ,” said Hrishikesh Choudhury, one of the authors.

Preliminary studies show that this fish is omnivorous. It can feed on algal and bacterial films in the cave. One living sample, nearly 6.8 centimetres long, was raised in the laboratory under a 12-hour light-dark cycle and fed with chopped earthworms for about three years.

The need for conservation

There are more than 20 species of Schistura in Northeast India, of which only two species – S. papulifera and now S. larketensis are eyeless. Both are native to Meghalaya and are believed to be obligate cave dwellers. Some other cave-dwelling fishes like Indoreonectes evezardi are known from Madhya Pradesh, but whether they are obligate cave dwellers is under debate.

In 1987, another species S. sijuensis was described from the Siju cave in the Garo Hills of Meghalaya. But, this fish had prominent eyes and distinct body pigmentation — features that are absent in loaches restricted to caves. “Probably, it was accidentally flushed and caught in Siju as the water level keeps fluctuating in the cave owing to frequent heavy rains in this area,” commented Sarma.

- papulifera, the closest blind relative of the new species was discovered from Synrang Pamiang cave at Umsngat entrance in 1999. But repeated attempts made by Mukhim to collect S. papulifera from this cave for this study via other entrances failed. “This entrance (Umsngat) is presently inaccessible as it has collapsed and remains blocked by boulders”, worries Mukhim. His expeditions through other entrances have revealed high siltation, pollution, and acidification of cave streams, which is possibly due to the accumulation of acid mine drainage from open cast coal mining and constant quarrying and blasting of limestone, and waste from cement plants situated on top of Pamiang cave system.

In December this year, Mukhim arranged a meeting of the villagers with the local forest officials, where they discussed ways and means to save this cave and the new species. “They are thinking of erecting a steel gate at the cave entrance for restricting entry. But more interventions for conservation are required and expected,” said Mukhim. This species is particularly threatened by mining, pollution and hunting in the adjoining areas since its population size is very small. “Luckily, limestone mining has been halted for some years now, but we still have a lot to do for its conservation,” signs off Sarma.

Source: Mongabay-India

An orbiting message of peace

An orbiting message of peace The Top Viral YouTube Videos of 2017

The Top Viral YouTube Videos of 2017 Meet R.N. Ravi, who is mediating peace with the Nagas

Meet R.N. Ravi, who is mediating peace with the Nagas The last Konyak headhunters of Nagaland

The last Konyak headhunters of Nagaland

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked (required)