By T. Keditsu

As a child, I would sit beside my father, listening to his stories – memories stirring with flavours and aromas, told in the language of meals. His love for food was something I absorbed both through his tales and the way food was central to our family’s life. For me, food was always available, a source of joy and pleasure. But I have come to realise, for my father, food was survival, a way to push back against a world that often left him wanting. His childhood was marked by scarcity, and the simple act of having enough to eat became a symbol of triumph, a small but significant victory over a difficult past.

My father grew up during a time when, to use a gynaecological metaphor in his honour, our society was in the labour pains of birth into modernity, beset with one tempest after another of conflict and upheaval. Food, for many in his generation, was a means of creating moments of joy and comfort in an otherwise hard existence. We must not forget that for many Nagas, our famed love for food is about reclaiming something essential, asserting our survival, and creating a sense of abundance in the midst of lack. Many led markedly less sheltered lives than the likes of my father, seeking asylum in our jungles, surviving groupings and the destruction of their fields and food stock. Food, if you could assign this term to a handful of rice cooked into a soup watery enough to feed whole families, and its consumption was simply a reminder that they were still in the world of the living.

As I grew older, I began to understand that food, for my father, was a language all its own. It expressed what words often could not: love, care, and a sense of belonging. This realization helped me see how food became central to our relationship. Where I found pleasure in taste and experience, my father found solace in the simple act of sharing a meal, of feeding the ones he loved. Much before he had to learn to hug his daughter and utter the English words, ‘I love you’ – to bridge a generational and cultural gap, food was his way of showing love, of building family.

Gary Chapman’s five love languages: gifts, words of affirmation, quality time, touch and acts of service have transformed the way I think about love, about how to read it when it is shown to me as well as how to express it in a way it can be understood by another. For my father, food was all of these five things in one—a wordless, deeply personal expression of his love for me and for the life he had built. Like most Naga families, each one in mine had their favourite part of the chicken. Mine was the liver. It was only after I married and started my own kitchen that I discovered my father’s preference for this same portion. To think that for all my growing years, he always saved it for me. To think that even now, whenever we eat together and he finds liver in the curry, he gives it to me. Growing up, for everything else, I would have to give a detailed justification for why I needed money. For food, all I’d have to say was, “Apuo, I’m hungry”, and he would send me money to go eat to my heart’s content.

When his health took a turn for the worse a few years back and it seemed like he had to change his diet drastically, I was struck by how this change would affect not just his lifestyle, but our bond. How do you reinvent a relationship that has been built around the shared experience of food and certain, particular kinds of food? Apuo and I were partial to marbled beef, pork fat, trotters, innards, mesenteric fat, fishing out marrow from femurs – the heavy stuff. Could we find new ways to express our love for each other, or would we need to craft an entirely new language (and menu) between us? This question haunted me. Yet, in the process of writing this book, I found the answer. The bond we share, forged over years of meals and conversations about food, transcends the specifics of what’s on the plate. It lives in the stories, the memories, and the ways we’ve connected beyond words.The Boy Who Loved Food is my way of preserving that connection. In writing this book, I have come to realize that food is complex, nuanced, and deeply intertwined with who we are. It is about survival, love and yes, memory.

Recently, I found myself in the middle of a disagreement over a deeply cherished memory – one that I have carried with me my entire life. The memory in question takes the form of a series of exchanges, quiet moments between my father and me. Bedtime stories with moral lessons, that conveyed both explicit and implicit reassurances of love and safety. Yet, someone suggested that this memory never happened. That it was something I had invented, a figment of my imagination. I have since wondered why such a remark had the power to wound me so profoundly.

The answer, I think, lies in understanding the role memory plays – not just in how we recall the past, but in how our recollections shape who we are. To connect the role of memory in shaping both individual subjectivity and the shared, collective experience of remembering, we can consider how Proustian memory operates as a bridge between past and present. Memory, for Proust, is not merely a passive recall of events but an active process that forms the foundation of identity. In his In Search of Lost Time, the madeleine, when dipped into tea, becomes more than a mere object; it triggers a flood of involuntary memories, revealing how deeply embedded our past is in our present.

Proust’s use of the madeleine illustrates how sensory experiences anchor memory in ways that exceed our conscious grasp. The taste of the madeleine pulls the narrator into a web of past experiences, reminding us that memory is both personal and relational. It is in this intertwining of self and other, past and present, that memory becomes not just a record of what was, but a reconstitution of who we are now, and how we relate to others. It is how Old man Sashi, in Temsula Ao’s short story, An Old Man Remembers, chooses to disclose his most traumatic memory with his grandson, while refraining from passing his most cherished one of first seeing a naked woman’s body as an innocent boy – an experience and memory he chooses to only share with his long deceased friend Imli.

In this sense, memory serves as a shared language, a way of binding people together, as we collectively participate in the act of remembering. The memories we share or withhold define the nature of our relationships and the person(s) we are in them. Memory is how we make sense of our subjectivity, how we navigate the complexities of personal and collective identity, how we relate to those who came before us and those who share in our present. Memory, after all, is history. It does not even have to be always factual. What matters is that through memory, we choose what to remember, and in that choosing, we create history.

The French historian Pierre Nora writes about lieux de mémoire – ‘places of memory’. He argues that memory is what creates history, not because it always aligns with fact, but because it represents what we, as individuals or societies, choose to carry forward. He observes that for “certain minorities,…without commemorative vigilance, history would soon sweep them away…The quest for memory is the search for one’s history.” In that sense, memory is not static, not a repository of pure fact. Instead, it is dynamic, constantly reshaped, constantly reinterpreted. An unfolding narrative that we write and rewrite in the presence of and with others. In this reshaping, it becomes both history and identity.

Thus, to question a memory is to question identity itself. The act of remembering is not merely about holding onto the past; it is about asserting the right to define ourselves in the present. So then, what happens, as did to me, if we are denied our memories, if they are censored, if the memories of some are privileged over others, if memories of a certain kind are deemed to be worth preserving and only through certain modes or if, we are forced to forget altogether?

As Nagas, this raises an urgent question: who are we, really? So much of our modern history has been remembered into writing by outsiders, chronicled through lenses not our own. Are we drawing the building blocks of our identity from our memories, or from the memories of others? And if from the latter, what does that make us?

I am currently reading Yogesh Maitreya’s memoir, Water in a Broken Pot. As a Dalit, his people’s history of violence and oppression far surpasses ours, both in its enormity and tenor. Yet, I find a resonance in the way he frames memory. He writes,

“In my life, my memories, unspoken and protected from the world, are the only source to see myself in history; or, to put it simply, my memories are my only history. This is one more reason why I rely on my memories to understand my history and also the history of others. My memories grow under my skin and they float in my blood cells. Protecting my history means protecting my memories.”

By this argument, for us to write our own histories, ourselves, we must first remember—individually and collectively. And not just remember, but fiercely defend those memories, and defend our right to put them on record. Yet, what kinds of memories are we to preserve? Only those of grand events and significant figures? There is value, yes, in such stories—those who have dedicated their lives to recording them deserve respect. But today, I want to make a case for the ordinary, the mundane, the personal.

It is in the small, everyday moments that the threads of a life are most tightly woven. These quiet memories – of family, of survival, of growing up in a world that often forgets to look at itself – are just as essential to our history. They are no less worthy of defence, no less important to our identity. In remembering these, we assert the right to tell our own stories, in our own way, and to shape who we are from the memories that are ours. Through memory, we can render unlovable people into lovable ones. Through memory, we can forgive.

This book, then, is not a grand history in the conventional sense. It’s not about an epic hero or a sweeping narrative. It is about my father, a man who, without a template or a model, managed to become a good father. It is also a quieter history of the Kohima of his youth, a window, so beautifully and thoughtfully illustrated by Akanito Assumi, through which our children can glimpse our recent past, where there were no irons and phones had dials. Pages from which we can pass on our history to our children of what life was like then.

In a world that often prizes the extraordinary, we forget that it can be just as noble, just as heroic, to simply survive. To do one’s duty, to love one’s family, to work hard without fanfare. And sometimes, a pyrrhic victory – one in which survival itself feels like a triumph -may be exactly what we need to remind us that endurance, especially in an increasingly chaotic world, can be its own kind of conquest. This book serves as a reminder of the many ways we can express love. That in the simple act of sharing or even talking about a meal, we often say more than words ever could.I hope this book will encourage us to actively cultivate our history through deliberate and conscious acts of remembering.Whether by writing or by speaking our stories in the ways of our oral tradition, let us enter into memory the quiet, persistent heroism of people in our lives. And finally, to the boy who loved, and loves food still, my beloved Apuo, a very happy birthday.

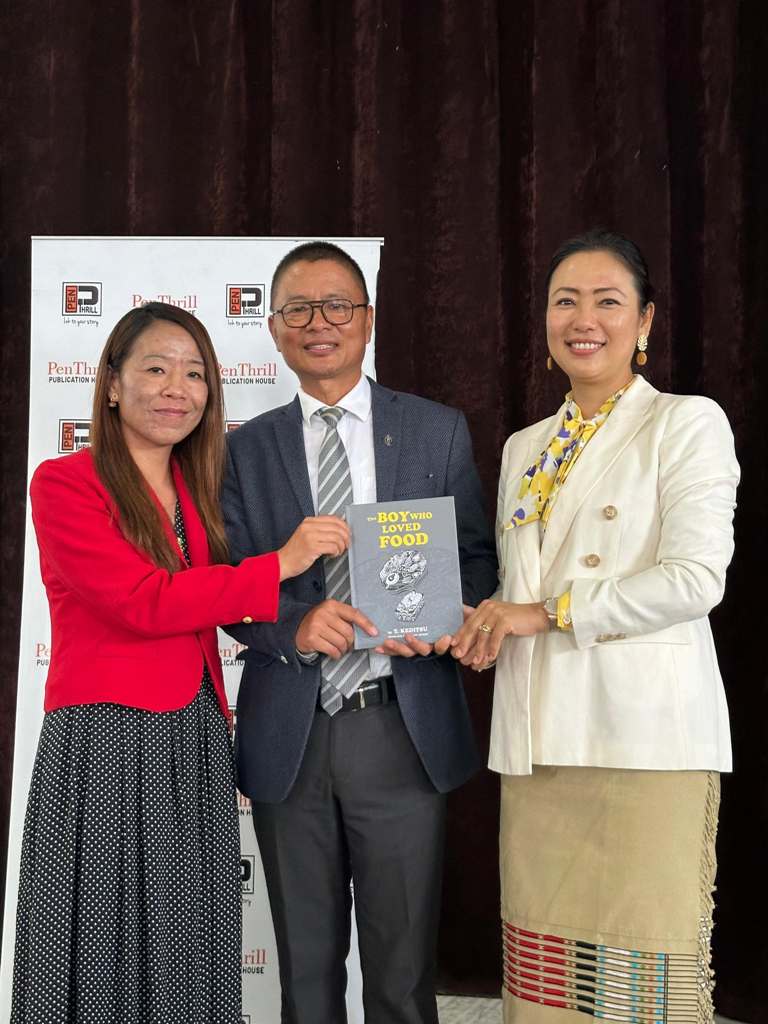

(The above thoughts was shared by the author T. Keditsu during the book release of The Boy Who Loved Food. The book is dedicated to her father Dr. Kezevituo Keditsu and was released on October 12, 2024. T. Keditsu is a feminist poet, academic, writer and educator. Her book is described as a portrait of her father’s life and a reflection on the bond that has tied the father and daughter together through their mutual love for food)

What Does Your Face Say About Your Health?

What Does Your Face Say About Your Health? The Top Viral YouTube Videos of 2017

The Top Viral YouTube Videos of 2017 Meet R.N. Ravi, who is mediating peace with the Nagas

Meet R.N. Ravi, who is mediating peace with the Nagas The last Konyak headhunters of Nagaland

The last Konyak headhunters of Nagaland

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked (required)